Holy Sepulcher complex

Type:

Churches,

Religious complexes,

Mosaics,

Sculptures

Date:

Originally dedicated in the mid-fourth century with later phases of rebuilding in the eleventh and twelfth centuries

Location or Findspot (Modern-Day Country):

Israel

Description:

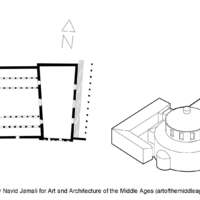

On the order of Emperor Constantine (r. 307–37), the Holy Sepulcher complex was begun in 326 to exalt the site of Christ's Entombment and Resurrection. The complex had a monumental entry leading to a five-aisle basilica with a western apse. Farther west was Golgotha, the site of the Crucifixion, rising in a colonnaded courtyard, and beyond that the tomb itself. The tomb was enclosed in the Anastasis Rotunda. The rotunda had twelve columns alternating with piers, a symbolic number corresponding to the apostles.

In 1009, Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah (r. 996–1021), who ruled the Fatimid Empire from Cairo, violated a treaty with the Byzantines and destroyed much of the Holy Sepulcher complex (as well as synagogues around Jerusalem). This was one of the events that galvanized crusader ideology. Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos (r. 1042–55) led the campaign to rebuild the Holy Sepulcher following negotiations between the Fatimids and the Byzantine Empire.

The work was done by masons from Constantinople working alongside local builders, and the resulting structure was much smaller than the fourth-century complex. It lacked the Constantinian basilica and was composed primarily of a new Anastasis Rotunda connected via a colonnaded courtyard to smaller chapels that had also been sites of veneration for centuries. These independent devotional sites accord well with developments in middle Byzantine architecture, which rejected large-scale early Byzantine churches in favor of smaller spaces better suited to changed liturgical needs, including multiple altars and devotional images that facilitated personal prayer and intercession.

A third rebuilding phase took place after the First Crusade (1096–99), at which time Jerusalem became a Latin kingdom. The renovations, completed during the reign of Queen Melisende in 1149, eliminated the small chapels and replaced them with a large choir that had an ambulatory and radiating chapels. A new dome united the choir, apse, and rotunda under one roof. Only one substantial mosaic survives from the period leading up to 1149. In the vault of a chapel at the top of Golgotha (today the Franciscan Calvary Chapel) is a mosaic representation of the Ascension. Although it has a Latin inscription, its style suggests mosaicists trained in the Byzantine tradition.

Two marble lintels, now in the Rockefeller Archaeological Museum in Jerusalem, have also survived from the twelfth century. They were originally part of the south transept facade, under two tympana. The western lintel has scenes from the life of Christ leading up to his death and resurrection. The eastern lintel has is non-narrative, covered only in inhabited vine-scroll designs. Historical photographs taken before their removal show the lintels in their original location.

The form of the fourth-century rotunda was the most enduring feature of the Holy Sepulcher throughout its different phases of rebuilding, and it inspired buildings across the medieval world at sites meant to evoke Jerusalem (see, for example, the entries on the Santo Stefano complex in Bologna and the Pisa Cathedral complex).

In 1009, Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah (r. 996–1021), who ruled the Fatimid Empire from Cairo, violated a treaty with the Byzantines and destroyed much of the Holy Sepulcher complex (as well as synagogues around Jerusalem). This was one of the events that galvanized crusader ideology. Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos (r. 1042–55) led the campaign to rebuild the Holy Sepulcher following negotiations between the Fatimids and the Byzantine Empire.

The work was done by masons from Constantinople working alongside local builders, and the resulting structure was much smaller than the fourth-century complex. It lacked the Constantinian basilica and was composed primarily of a new Anastasis Rotunda connected via a colonnaded courtyard to smaller chapels that had also been sites of veneration for centuries. These independent devotional sites accord well with developments in middle Byzantine architecture, which rejected large-scale early Byzantine churches in favor of smaller spaces better suited to changed liturgical needs, including multiple altars and devotional images that facilitated personal prayer and intercession.

A third rebuilding phase took place after the First Crusade (1096–99), at which time Jerusalem became a Latin kingdom. The renovations, completed during the reign of Queen Melisende in 1149, eliminated the small chapels and replaced them with a large choir that had an ambulatory and radiating chapels. A new dome united the choir, apse, and rotunda under one roof. Only one substantial mosaic survives from the period leading up to 1149. In the vault of a chapel at the top of Golgotha (today the Franciscan Calvary Chapel) is a mosaic representation of the Ascension. Although it has a Latin inscription, its style suggests mosaicists trained in the Byzantine tradition.

Two marble lintels, now in the Rockefeller Archaeological Museum in Jerusalem, have also survived from the twelfth century. They were originally part of the south transept facade, under two tympana. The western lintel has scenes from the life of Christ leading up to his death and resurrection. The eastern lintel has is non-narrative, covered only in inhabited vine-scroll designs. Historical photographs taken before their removal show the lintels in their original location.

The form of the fourth-century rotunda was the most enduring feature of the Holy Sepulcher throughout its different phases of rebuilding, and it inspired buildings across the medieval world at sites meant to evoke Jerusalem (see, for example, the entries on the Santo Stefano complex in Bologna and the Pisa Cathedral complex).

Relevant Textbook Chapter(s):

2,

6,

7

Image Credits:

Wikimedia Commons, Linda Safran, Navid Jamali