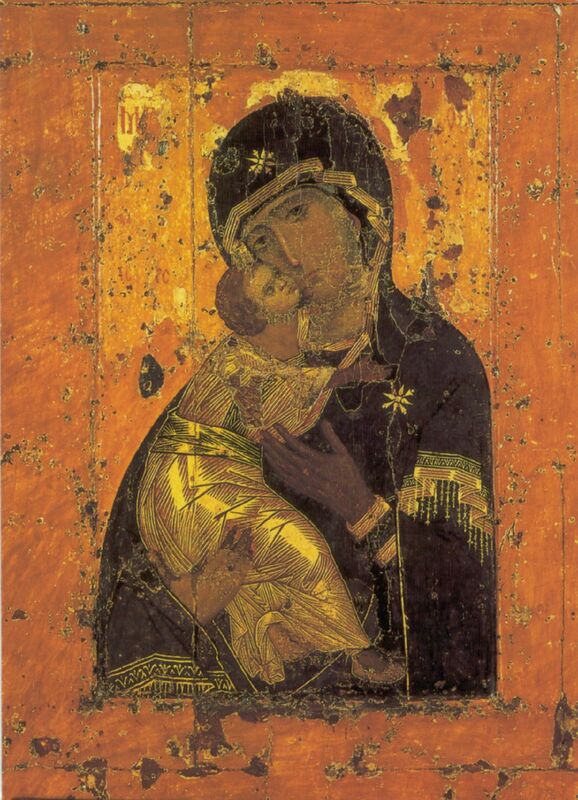

Vladimirskaya

Type:

Icons

Date:

Twelfth century and later

Dimensions:

104 × 69 cm

Description:

This early twelfth-century Byzantine processional icon may have been a diplomatic gift to celebrate the wedding of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos's nephew to a Kyivan princess named Dobrodeia; she was escorted to Constantinople in 1122 and became well known for her knowledge of herbal medicine (her sisters became queens of Norway, Denmark, and Hungary). Alternatively, it may have been a Byzantine gift of ca. 1131 to Andrej of Bogoljubovo (1111–74), prince of Rostov-Suzdal and later grand prince of a new capital at Vladimir. Russian chronicles say that the icon arrived in Kyiv and levitated in its church, signaling a wish to move elsewhere. It was taken to Vladimir in 1161, clad in precious metals, gems, and pearls, and and was installed in a purpose-built cathedral dedicated to the Koimesis. Since then has been known as the Vladimirskaya or the Virgin of Vladimir. It is considered the palladion—the protective image—of medieval Rus' because, among other miracles, it saved Moscow from an attack by Timur (r. 1370–14-5) in 1395. The icon is now in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

This tender image of the Theotokos and Christ child is known as the Eleousa (Russian Umilenie), which means tenderness, evident in the way the mother and child interact affectionately while Mary, anticipating Jesus's fate, looks sadly out toward the viewer. The Child's upturned left foot and the arm around his mother's neck may have originated with this icon. Mary wears her traditional maphorion, a dark robe edged in gold and with gold stars on her head and shoulders. Jesus's garment is richly ornamented with chrysography (golden highlights). Yet scientific study in 1918 revealed that few parts of the painted surface belong to the original twelfth-century image. The two faces and the shoulder and arm of Jesus are original, painted on the linen that once covered the five wooden panels that compose the icon.

Mary's left hand and Jesus's right hand have completely lost their pigment; they are worn through to the wood because they were constantly touched and kissed by the Orthodox faithful. Pious viewers evidently hesitated to touch the faces. When Byzantine icons became worn or damaged, attempts were often made to preserve them. The Vladimirskaya was repainted after 1237, when it was burned in the Mongol attack on Vladimir and its metal cladding was forcibly removed. This damaged everything except the faces, which had never been covered by metal. Later restorations occurred in the fifteenth century, when the reverse of the bilateral icon was painted with an altar and instruments of Christ's Passion, and in the sixteenth, and nineteenth centuries. Nevertheless, the icon retained its authenticity and spiritual power and helped affirm religious and political ties between Byzantium and Rus'.

This tender image of the Theotokos and Christ child is known as the Eleousa (Russian Umilenie), which means tenderness, evident in the way the mother and child interact affectionately while Mary, anticipating Jesus's fate, looks sadly out toward the viewer. The Child's upturned left foot and the arm around his mother's neck may have originated with this icon. Mary wears her traditional maphorion, a dark robe edged in gold and with gold stars on her head and shoulders. Jesus's garment is richly ornamented with chrysography (golden highlights). Yet scientific study in 1918 revealed that few parts of the painted surface belong to the original twelfth-century image. The two faces and the shoulder and arm of Jesus are original, painted on the linen that once covered the five wooden panels that compose the icon.

Mary's left hand and Jesus's right hand have completely lost their pigment; they are worn through to the wood because they were constantly touched and kissed by the Orthodox faithful. Pious viewers evidently hesitated to touch the faces. When Byzantine icons became worn or damaged, attempts were often made to preserve them. The Vladimirskaya was repainted after 1237, when it was burned in the Mongol attack on Vladimir and its metal cladding was forcibly removed. This damaged everything except the faces, which had never been covered by metal. Later restorations occurred in the fifteenth century, when the reverse of the bilateral icon was painted with an altar and instruments of Christ's Passion, and in the sixteenth, and nineteenth centuries. Nevertheless, the icon retained its authenticity and spiritual power and helped affirm religious and political ties between Byzantium and Rus'.

Relevant Textbook Chapter(s):

7,

8,

10

Image Credits:

Flickr